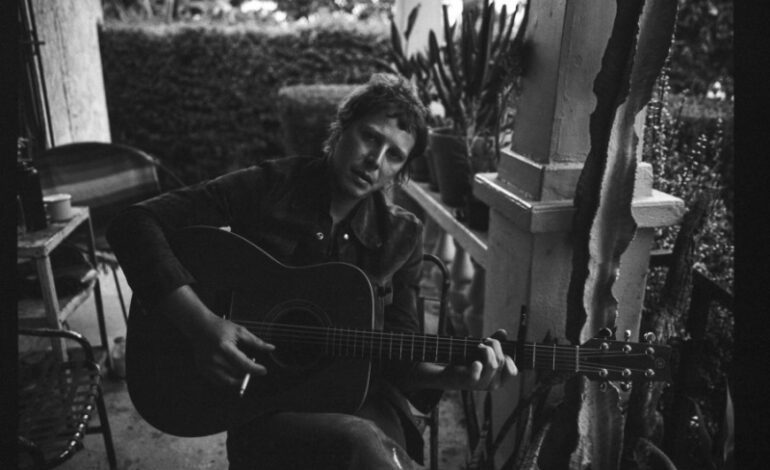

St. Lenox on Work, Ambition, and Realism in “Ten Modern American Work Songs”

In this interview, St. Lenox opens up about the inspirations and personal experiences behind Ten Modern American Work Songs, a deeply reflective album exploring themes of ambition, education, and the evolving challenges of the modern workforce. With a background that spans from classical violin studies at Juilliard to earning a PhD in philosophy and becoming an attorney, St. Lenox brings a unique perspective to the complexities of professional life.

The conversation touches on the struggles of balancing career and family, as explored in the lead single “Rudy” and its accompanying video, “How to Get a Table at Tatiana.” St. Lenox also discusses the disillusionment with higher education and the economic pressures facing Millennials and Gen-Xers, along with a desire to provide a realistic portrayal of modern work life—without prescribing solutions or oversimplifying the journey.

Far from a universal statement, the album offers a lens into specific generational experiences, inviting listeners to engage with the material on their own terms. As St. Lenox puts it, “It’s enough that they feel what I felt at big moments in my life, and how they process that is up to them.” Check out our exclusive interview below:

1. Your upcoming album, Ten Modern American Work Songs, explores themes of ambition, education, and the struggles of the modern workforce. What inspired you to focus on these topics, and how do they reflect your personal experiences?

I don’t initially set out to write albums, I generally write songs, and because the songs are about my life, and I live and breathe in America, there are themes that start to emerge out of that. As it happens, I had a number of songs that were broadly about work, and so it made sense to write a number of new songs in that vein to fully explore that angle. Over the last 20 years, I transitioned from being a graduate student in Philosophy to going to law school and eventually becoming an attorney. That transition was very difficult and draining and risky, to completely change what I thought was my life’s trajectory (for the second or third time, depending on how you count it) and I did it for reasons that relate to the reasons why many Millennials and Gen-Xers find the modern world of work exasperating. In any case, I wrote songs throughout that period, and when you sum up your life experiences in such a period, there’s a good chance you’ll have a record that is about that I suppose.

2. The lead single “Rudy” tackles the tradeoffs between professional ambition and family life. What message do you hope listeners take away from the song and its playful video, “How to Get a Table at Tatiana”?

I don’t have messages per se. I mean, my 20s and early 30s had a lot of tradeoffs between professional and artistic ambitions. I did also have many struggles with achieving the kind of family life that I have now. The stories in Rudy are drawn from my life but aren’t exactly my story (though I did forget my mother’s birthday when I was working particularly hard, and I did hate that). I think the song and the video portray a lot of the difficulties and challenges that I faced in my 20s and 30s (or very similar difficulties and challenges). But it’s not really my place to tell people what to take from that – its enough that they understand it as a real phenomenon and understand the struggle in a visceral way.

One could take from Rudy the message that people need to prioritize family over social status. But I think that’s probably too broad a conclusion to draw. The video sort of takes a different position – it suggests that domestic goals and social status maybe aren’t incompatible, but maybe in a way we didn’t conceive of initially. The protagonist there is frustrated having to move out of the big city, but finds a way to have a taste of high society by learning to cook at home. Does that mean that all apparent tradeoffs are merely illusory? No, that would also be too broad a statement. But having both stories gives people a framework for thinking about life tradeoffs – something beyond “follow your dreams!”.

3. You have a remarkable background in both music and academia, from studying violin at Juilliard to earning a PhD in philosophy and attending law school. How have these diverse experiences shaped your songwriting and the themes you explore in your music?

I mean, the short answer is they have shaped my songwriting a lot. Classical music has had a big influence on my songwriting, but I don’t think a lot of people will be able to really understand that, witihout listening to a lot of classical music. A lot of my sense of phrasing and interpretive approach to melody comes from that. Philosophy I think allowed me to think more abstractly about songwriting, which has allowed me to take my own path as a songwriter. Law school hasn’t shaped my songwriting a goddamn bit.

4. You’ve mentioned wanting Ten Modern American Work Songs to provide a kind of realism about work life today. What aspects of the modern American workforce do you find most urgent to address, and how do you hope your music motivates listeners on an ethical and political level?

I mean I think for a lot of people I know, we were told to invest time and money and years into education, as an investment, only to have the industry drain the value out of the investment, for its own profit. For instance, I went into graduate school with the idea that there were professor positions available at the end of the journey, but then schools decided to convert professor positions into low-paying adjunct teaching positions. And so I was left in a compromised position after receiving my PhD. Law school, I think there was a similar thing, where the cost of law school has been hiked up to the heavens for no obvious legitimate reason. Law school is extremely expensive, but the education we got in law school was not great. Many professors give the exact same lecture, word-for-word, that they’ve given for decades. Many of them don’t actually teach the skills that you will use in the real world afterwards. Most professors in law school do not even have a PhD, which makes them ineligible to teach even freshman level college courses. Why law school ends up costing more than undergraduate is a complete mystery – except that the schools know that many graduates make big salaries afterwards and can afford to pay. So the explanation is that law schools took what was an investment, and decided to make it less of an investment by shifting the value from students to themselves. I know many students had family pay for their schooling, and some people had scholarships to pay for schooling. But for someone like myself, who had to pay my own way, there was definitely a risk – and while things turned out okay for me, it could have also turned out very badly for me too.

I think realism as a project is a few different things. It’s about focusing on aspects of life that aren’t necessarily covered by popular music, because popular music fails at representing reality in some significant way. It’s also about portraying those aspects of life in a vivid and realistic way, that allows the listener to see the value of those aspects of life. I don’t have specific messages or commands to listeners to tell them how to respond to my music – for me its enough that they feel what I felt at big moments in my life, and how they choose to process that practically in their lives is for them to decide.

5. As a progressive, queer artist, how does your identity shape the way you approach storytelling in your music, especially when tackling universal themes like career aspirations and burnout?

My queerness doesn’t shape my storytelling on this record, just like my being Asian doesn’t really shape the stories on this record. And I want people to be able to approach the record, without qualifying it in their head as being a gay or an Asian-American record. There are other records that I have, where those identities become more important. (For instance, my queerness is much more relevant to Ten Songs of Worship and Praise, and my Korean-ness is much more relevant to Ten Hymns from My American Gothic). And we should allow queer artists and people of color, and women, to serve the definitive statements on the Big Issues of our Time, as opposed to leaving them to straight white men.

I would say that the themes on the record don’t speak to universal themes like career aspirations and burnout. I mean – there is definitely a connection that the stories have to those themes. But the record is very much about Millenial and Gen-X struggles with work – which is why I call it Ten “Modern” American Work Songs. Fifty years ago, people had career aspirations and burnout, but they didn’t broadly struggle with the education industry in the way that we do now. This record is not going to speak the truth of a steelworker 50 years ago. The union song on the record (“Lust for Life”) is about graduate students in the humanities, not people working manufacturing jobs – and that’s what sits this record in a specific place and time.

Check out “Rudy” below: